Melanie Asmar, Chalkbeat Colorado

On the first day of summer school in Denver, six incoming first graders took a spelling test. Using long pencils with unsmudged erasers, they spelled noche, jugo, pequeño, and vecino.

“Número tres es la palabra — es un poco larga — ‘pequeño,’” the teacher said, warning the students that the third word she wanted them to spell, the Spanish word for “small,” was a bit long.

A girl with glasses and an oversized pink bow looked down at her paper and sounded it out.

“P–p-p-pequeño,” she whispered to herself as she wrote a “p” next to No. 3.

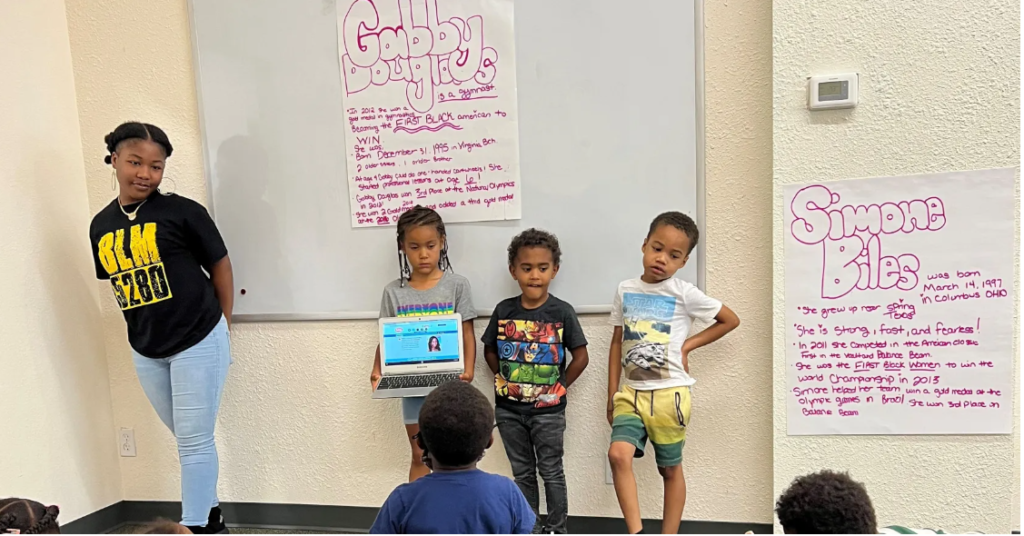

Because the 6- and 7-year-olds are enrolled in Denver Public Schools’ bilingual education program, they learn spelling, reading, and math in Spanish. As they build core academic skills, they also learn English, and over time transition to learning less and less in Spanish.

Denver parents and educators fought for this kind of bilingual programming — known as transitional native language instruction or TNLI — and a federal court order requires the district to offer it at every school with at least 60 students who speak Spanish and are learning English.

But Denver’s bilingual programming faces a big threat: too few students at a growing number of schools.

High housing costs and falling birth rates are driving down public school enrollment, especially in Denver’s historically Latino neighborhoods. That makes it harder for elementary schools to fill bilingual classrooms, and educators are making compromises, like combining two grades into one classroom, that don’t work as well for students. The district already moved to shut down four small TNLI — pronounced “tin-lee” — programs earlier this year before backing off.

The district is also considering closing some schools altogether. More than half of the schools that meet recommended criteria for potential closure house TNLI programs. The 15 schools account for nearly a quarter of the district’s 65 schools with bilingual classrooms.

Consolidating schools might allow for more robust programming, but that carries its own cost.

“This school is part of our community,” Yuridia Rebolledo-Duran, a mother of two Colfax Elementary students, said in Spanish at an April rally outside the threatened school. “It is very important for us as parents that our children can speak two languages.”

Research largely supports the efficacy of bilingual education. In Denver, English language learners who become fluent in English have historically done well on state standardized tests. Denver’s top school administrators support it, too.

“We are very sad by the fact that declining enrollment is impacting our bilingual schools,” said Nadia Madan Morrow, a former bilingual teacher who led the district’s multilingual education department until being promoted recently to chief academic officer. “We’re working hard to figure out how to deliver native language instruction in schools that are continually shrinking.”

But that wasn’t always the case.

Some educators used to punish students who spoke Spanish in class, a practice that led to fierce protests. In 1980, a local group called the Congress of Hispanic Educators sued the district for violating the rights of English language learners.

A federal judge found the district at fault. In 1984, Denver entered into its first consent decree, a legally binding agreement to provide bilingual education. It has been modified twice since.

The most recent version, in effect since 2013, says the district must provide TNLI programming at schools with more than 60 Spanish-speaking English language learners, employ qualified bilingual teachers, and use high-quality Spanish-language curriculum and tests.

“Our bilingual parents want their children to end up being bilingual,” said Kathy Escamilla, a member of the Congress of Hispanic Educators who is a retired University of Colorado professor and researcher of bilingual education. “They want the opportunity for their culture and history to be represented.”

The consent decree applies to only Spanish-speaking students, who make up the largest portion of Denver’s English language learners. Other English language learners are taught entirely in English, sometimes with the help of teachers or tutors who speak their language. Arabic and Vietnamese are the second- and third-most common native languages.

The number of English language learners in Denver has gone up and down for a decade, as has the number of students enrolled in TNLI programs and the number of schools that offer them.

In the past, the district would revoke the TNLI status from any school serving fewer than 60 Spanish-speaking English language learners over a period of time, Madan Morrow said. But when the district last winter tried to do that at four elementary schools — Colfax, Cheltenham, Traylor, and Schmitt — the Congress of Hispanic Educators pushed back.

Three of the four schools have lost so many students that they’re at risk for closure in the near future. That heightened the communities’ concerns about losing TNLI.

A year ago, the elected Denver school board passed a resolution that said parents, teachers, and others should help develop a plan to consolidate small schools. Denver schools are funded per pupil, and small schools struggle to afford things like electives and mental health staff.

The district listed 19 schools that would participate in the process. The goal was for the communities at those schools to come up with ideas for how to consolidate.

But the list caused a panic, and Superintendent Alex Marrero scrapped it.

Switching tactics, the district this year assembled a declining enrollment advisory committee and tasked it with coming up with criteria for when to close schools with low enrollment.

The committee revealed its proposed criteria last month: Elementary and middle schools with fewer than 215 students next school year, as well as schools with fewer than 275 students that expect to lose 8% to 10% of students in the coming years, should be considered for consolidation, as should financially struggling independent charter schools.

Twenty-seven district-run schools had fewer than 275 students this past year. Like the 19 schools on the original list, most of the 27 schools serve student populations that are more than 90% students of color and more than 90% from low-income households.

Fifteen of the 27 schools are TNLI schools, including Colfax Elementary, where parents and advocates held a rally in April against closing their school. Several mothers said they live close by and walk their children to school because they can’t drive.

“It worries me because how am I going to take the children to other schools?” Cecilia Sanchez-Perez, a mother of two Colfax students, said in Spanish.

Escamilla of the Congress of Hispanic Educators was at the rally, too.

“We understand that DPS is facing some difficult decisions regarding budgetary decisions and declining enrollment,” she said. However, she added, “too often these types of changes disproportionately impact Black, brown, and poor communities.”

If the district removed the TNLI designation from Colfax and the three other schools, advocates worried students could be left without bilingual programming. Even with free busing to a nearby TNLI school, families might hesitate to leave the schools they know and love.

The Congress of Hispanic Educators was also skeptical of the district’s enrollment projections and concerned that parents hadn’t been consulted, Escamilla said.

Because of the pushback, Denver agreed to keep the TNLI designation at Colfax, Cheltenham, Traylor, and Schmitt. But Madan Morrow said that the dwindling numbers of Spanish-speaking students mean programming there may not be as robust.

Many of Denver’s TNLI schools still have healthy enrollment. But at schools without enough Spanish-speaking students in each grade, bilingual programming looks different.

What often happens, educators said, is that schools mix two grade levels in one classroom, which isn’t ideal academically or popular with parents. Or schools combine native Spanish with native English speakers, a difficult assignment for even the most veteran educators.

Kim Ursetta, who teaches bilingual preschool at Traylor, taught a combination of native English and native Spanish speakers this past year for only the second time in her 28-year career.

“It’s hard to pull off,” she said. “You’re always jumping between languages, and no matter what, you’re only getting them half of the time you’d normally have.”

If combining students isn’t possible, schools sometimes put Spanish speakers in English-only classrooms and pull them out of class to learn certain subjects in Spanish. That can leave students feeling ostracized or cause them to miss fun elective activities.

It’s something school board member Carrie Olson, who was a bilingual teacher in Denver for 33 years before being elected to the board, saw firsthand. Olson is concerned with how declining enrollment is affecting TNLI programs and has repeatedly asked that the board discuss it.

Madan Morrow said principals and district staff are working on plans for next school year.

“We know any amount of native language instruction is better than none,” she said. “What we are trying to figure out with these four schools is, ‘What is the sweet spot? How much can we give them so it’s beneficial without them being in a pullout setting all day long?’”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.