By Alan Gottlieb

Over the past five years, Brandon Pryor has been the most consistent and vociferous critic of Denver Public Schools leadership. He uses blunt, forceful language, with all the subtlety of a sledgehammer.

He does this consciously and deliberately. He ruffles feathers and hurts feelings. “It’s eye-opening. It’s shocking some of the stuff I say, but that doesn’t make it wrong,” Pryor told me this week. “I do this because I feel these people are oppressing our black community and they need to be called out.”

Pryor, who is Black, called former Superintendent Tom Boasberg a racist and a white supremacist. He called Boasberg’s successor, Susana Cordova, an upholder of oppressive systems. He has had well-publicized run-ins with a number of school board members over the years.

Until now, however, district officials and board members have taken the harsh words in stride, essentially letting Brandon be Brandon, as much as they might have disliked his words.

Last week, however, that all changed. Pryor says armed, uniformed Denver security officers showed up at his home to hand-deliver an eight-page letter from the district, informing him he had been banned from DPS buildings and meetings, including school board public comment sessions, for the next two years. The exception is the schools his children attend.

Denverite reported that “the letter DPS sent Pryor last Tuesday cites “repeated abusive, bullying, threatening, and intimidating conduct directed at staff of the Denver Public Schools” as the reasoning behind the ban. The letter calls the language “inappropriate,” “harmful” and in violation of DPS policies.”

Pryor denied that he has threatened anyone, other than a community gadfly who made disparaging remarks about him and his family on Facebook. To that person, Pryor wrote that if he said those things to his face “you are going to have a problem.”

“That person is not even a DPS employee,” Pryor said.

So why ban him now? Why has arguably the most racially diverse administration in DPS history decided that Pryor has to be silenced? Pryor says it’s a result of thin skin and fragile egos. And he seems to have a point.

Free speech can be hard to hear at times, particularly when blistering language is aimed at you. But if you’re in a public-facing position, sometimes you just have to take it.

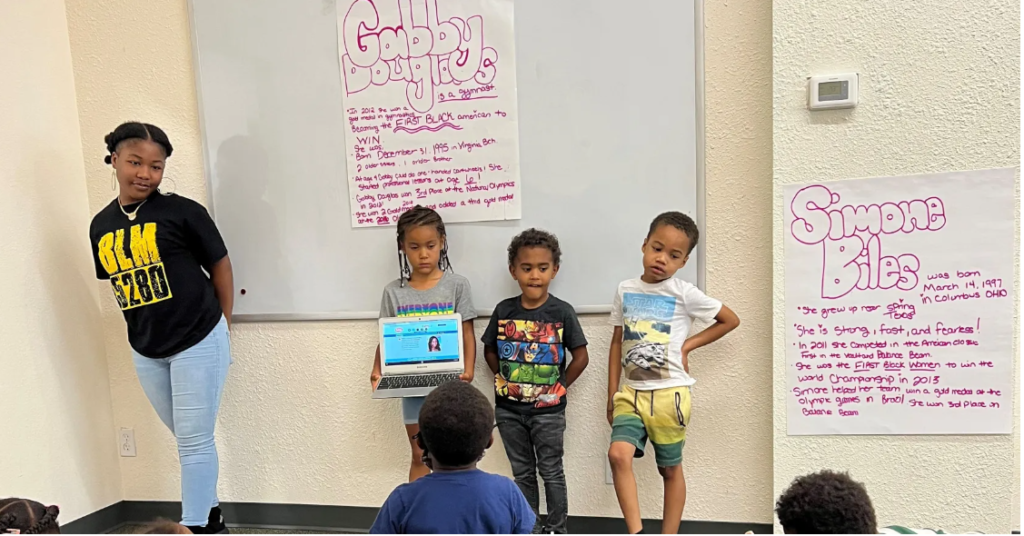

Pryor was a key player in getting the Robert F. Smith STEAM Academy, a district-run high school, approved and opened. It’s a school founded on the principles of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and its particular aim is to provide Black children with a rigorous, culturally responsive education.

In recent months, Pryor has been increasingly vocal about a bad deal he feels the school has gotten from the district. It started when the district listed the wrong address for the school on school choice forms in the run-up to the school’s first year.

More recently, he has complained that the Montbello building where it is located is ill-suited to the mission, that meals brought in are substandard, and the DPS is undermining its success, either deliberately or through neglect and incompetence.

As his anger has grown, his rhetoric has escalated. During the monthly comment session before the school board earlier this month, Pryor called out Superintendent Alex Marrero and senior members of his cabinet – four Black men – and said they should be fired.

It was later that week that Pryor was banned.

Pryor has also been one in a chorus of voices of different races decrying DPS’ decision to trademark a podcast started by four Black female students. The district has said it made the move to protect its intellectual property. Pryor said he sees it as another way to keep Black students from thriving.

“I’ve called some of the folks in leadership sellouts because they look like I do, but they’re making decisions that are harming our communities,” Pryor told me. “They need to be fired. They’re grossly incompetent and their actions towards me are proof of that. You don’t have to be white to be an upholder of a system of oppression.”

Pryor said he was also angered by the tone of a letter Marrero sent to the community after last week’s public comment session. In that letter, Marrero detailed the district’s position on several issues that were focal points during the public comment session, including the Know Justice Know Peace podcast and the STEAM school.

“We encourage you to continue sharing your voice and perspective, however, we ask you to seek the facts and share the truth,” Marrero concluded the letter.

“The tone of it was extremely dismissive, like we know what’s right, we have the truth,” Pryor said. “The message was that what you, the community, is saying is not right. It was completely discrediting what the community is saying.”

Pryor said he will mount a legal challenge to fight the ban. “They are trying to silence me and deprive me of my First Amendment right to free speech,” he said. “All because I’m speaking out for the rights of our black children. That’s all I have been doing is trying to speak up for our black children. And so I get banned.”

There’s no doubt that Pryor is a lightning rod and plenty of people will be unhappy that I’ve written this piece defending him. But as a long-time journalist, I get my back up whenever public officials try to muzzle someone, regardless of how offensive they find that person’s words to be.

Do better, DPS.

Alan Gottlieb is Boardhawk’s editor. Alan has been a Denver-based journalist for more than 30 years. He covered DPS for the Denver Post in the mid-1990s, worked as an education program officer for The Piton Foundation, and co-founded Education News Colorado and Chalkbeat. For the past five years, he has worked as a contract writer and communications consultant.