The Springsteen sideman hopes his growing TeachRock program will help curb a dropout crisis he calls ‘intolerable and scandalous.’

Keep The 74 free with a donation during our Fall campaign.

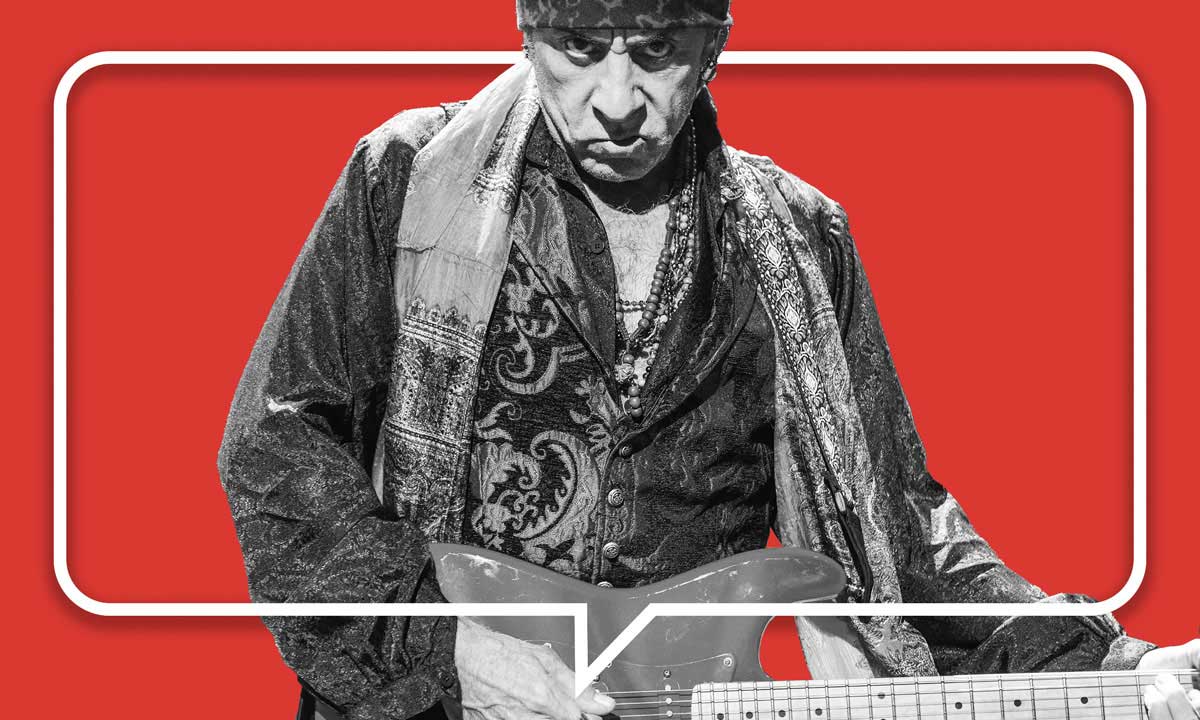

Steven Van Zandt is not only one of the busiest men in show business. The composer, arranger, guitarist and longtime Bruce Springsteen sideman is also a transformational educator.

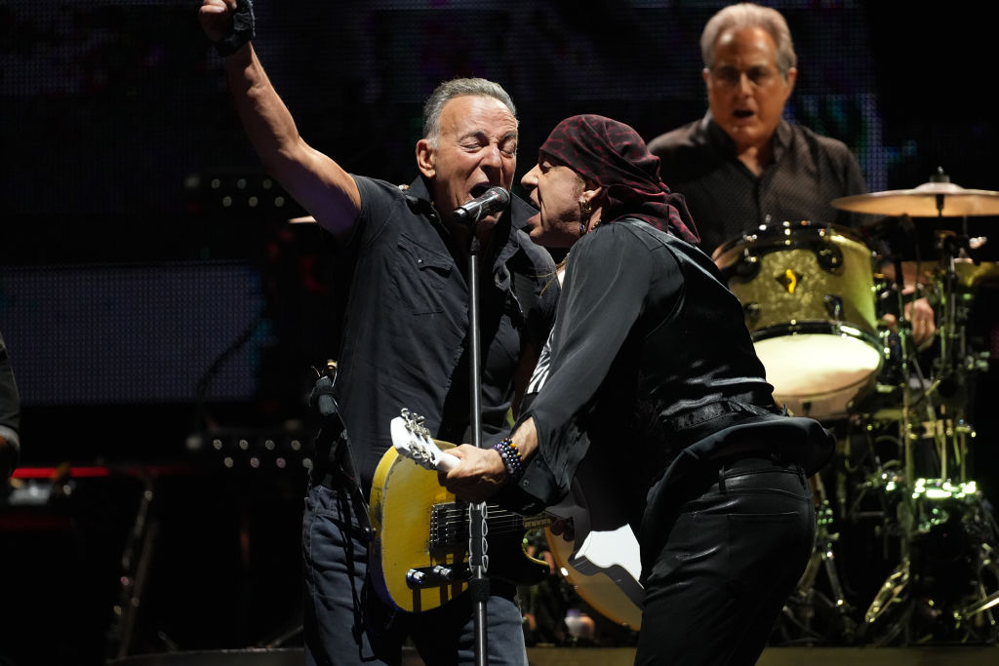

A record producer and music historian, Van Zandt has been a member of two well-known rock bands: Springsteen’s legendary E Street Band and the influential Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes. A fierce promoter of American popular music, he’s in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Van Zandt found a new generation of fans in 1999 as TV mob consigliere Silvio Dante on “The Sopranos.” Twelve years later, he co-wrote, executive produced and starred in “Lilyhammer,” Netflix’s first original scripted series.

Oh, and before that, he landed a blow against the apartheid-era government of South Africa by organizing the all-star 1985 recording session that produced the protest anthem “Sun City,” in which major artists vowed they’d boycott its eponymous segregated resort.

But in 2006, Van Zandt launched TeachRock, a free, comprehensive U.S. history course for K-12 students that uses pop culture to teach about the period between World War II and the near-present.

The lessons now number in the hundreds, and encompass every grade level. One middle-school lesson uses poetry and music to explore ways in which the United Farm Workers movement and Dolores Huerta contributed to civil rights struggles and the feminist movement. Another, for younger students, uses documentary footage and folk music to help students understand the environmental legacy of mountaintop removal by coal-mining companies in Appalachia. Students eventually create their own folk ballad about an environmental issue of their choice.

This fall, the program will get a big boost as the Bruce Springsteen Archives and Center for American Music at Monmouth University, a wide-ranging collection of materials related to Springsteen in particular and popular music more generally, partners with Van Zandt’s nonprofit. The partnership gives TeachRock access to a vast array of original material and allows it for the first time to bring teachers to the archives for workshops and events.

“We’re really excited to work with them to build bridges between classrooms and the center,” said Executive Director Bill Carbone. He noted an upcoming symposium in October celebrating the 50th anniversary of the release of Springsteen’s sophomore effort, “The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle.” The event will feature original members of the E Street Band.

TeachRock is already in more than 30,000 schools in all 50 states, and a recent efficacy study that interviewed participants found that, by far, students were most engaged when they were “learning something new that opened students’ eyes or caused them to think of something in a way they hadn’t before.”

With the current Springsteen tour on hiatus due to illness — the band leader is being treated for a peptic ulcer — Van Zandt, 72, sat down this month with The 74 from his New York City home and talked about his program, his musical education and the legacy that baby boomers leave behind.

“I think it’s an obligation,” he said. “I really do feel it’s a responsibility for us to pass along something that was better than we had.”

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: One of the things I remembered from talking to you in 2020 is asking about this quote of yours, where you said, “I had a vacation once in 1978, and I didn’t like it.” And I wonder: It’s three years later. Have you had a vacation yet? And if so, did you like it?

Steven Van Zandt: No, but I’m starting to understand the concept (laughs).

So you’re easing into it?

Yeah. I’m discovering these things called weekends. And all kinds of revelations are coming to me late in life.

Excellent. Obviously, we’re going to talk about the work you’re doing in education. But I wanted to ask you about your own musical education. I wanted to actually spool back a little bit and ask about your earliest musical memory.

My earliest musical memory? That’s a good one. I want to say what comes to mind is the Mickey Mouse thing. “Fantasia,” was it?

Did you have a lot of music in your house when you were a kid?

Not really. My father was a part of a barbershop quartet. So I was exposed to that quite young. That may have planted my love of doo-wop. But around the house, not so much.

You talk about the Beatles a lot and their Ed Sullivan Show debut on Feb. 9, 1964, and the effect that had on you. That’s such an important part of your story.

What we call the British Invasion was a major turning point in my life. Pop music has always been around. We actually had good pop music in the fifties and early sixties. I started buying some singles a few years before the British Invasion happened. I was buying “Duke of Earl” and “Pretty Little Angel Eyes” and The Dovells’ records, The Four Seasons.

But I wasn’t really particularly interested in doing it until the British Invasion happened. There weren’t that many bands in America back then. If there was a band, it was mostly an instrumental group. You went to your high school dance, it was an instrumental group, usually, and a sax player would be the leader usually and then maybe put the saxophone down for like one song where he’d sing.

Then suddenly, here comes the Beatles. And then The Dave Clark Five and Herman’s Hermits and then The Stones and The Who and the Kinks and the Yardbirds and all of the British Invasion bands — four or five guys all singing and playing their own instruments and eventually writing their own songs, which was a major, major change. Up until then, most of the artists, with a few exceptions like Little Richard and Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, Buddy Holly — the major pioneers — were [not] writing their own songs.

Keep in mind that rock wasn’t mainstream, really, until the British Invasion. Mainstream pop artists were mostly not writing their songs. So you had songwriters and arrangers and producers. It took an army to make a record in those days. Publishers were involved in all kinds of different facets of the business.

Then it all came together when you had a self-contained band like The Beatles. They just changed everything. They changed the entire configuration of the business. Technically, publishers were no longer relevant, because publishers’ main job was to expose a writer’s music to the world in the form of sheet music. They literally would publish physical music and they would make those piano rolls, back in the 1880s or whenever. They were popular.

And with a band singing their own songs — in other words, marketing themselves — the whole publishing thing would soon transform itself into mostly administration, which was collecting the music and collecting the money for these self-publishing artists.

[The Beatles] changed the whole culture. It wasn’t just me and other freaks, misfits and outcasts who had no real place in society. There were a lot of us who just couldn’t find our way through the options we were being offered. It was really a blessing to us to have the exposure [to] this whole new world. The entire culture changed into a band culture. Kids, when they were going out at night, you might go to a movie, mostly drive-ins in those days. And if you weren’t going to the drive-in, you were going to see a band.

For our generation — and we were the luckiest generation ever — there were all kinds of teenage band activities. It wasn’t just the bars. The bar culture had bands. But before you got to the bar culture, literally teenagers, 12, 13, 14 years old, you’d go to beach clubs, you’d go to V.F.W. halls, you’d go to your high school dances, you’d go to clubs that were built for teenagers, literally teenage discotheques, as they were called before disco happened. You would go out as a kid. Your parents would drop you off, and you’d go see a band.

But it was bigger than that. The entire culture was electrified. Suddenly, our generation had a soundtrack that was really quite significant. The fifties generation, the generation before us, also had a wonderful soundtrack going on, but it seemed to be a little bit more temporary in some ways.

Our artists grew, our artists evolved. This one aspect that the Beatles brought gets underreported — and Bob Dylan was right there with them — but the Beatles actually introduced the idea of evolution in popular art, which was not a thing. Popular art was: If by some miracle you had a success, your job was to match that success as often as possible and as closely as possible.

The great example is the record called “The Twist.” And then you follow it up with “Let’s Twist Again.” (Laughs.)

Right. No shame at all!

The perfect template for what was the pop music methodology.

And for the Beatles, I think, it was just boredom because they’d been doing it so long. They had one of the longest gestation periods between starting and arriving. Only the E Street Band was longer than the Beatles, I think. It took us like seven years, but them, like five years — four or five years of working in bars, working in the clubs, absorbing all the material. In those days, they knew every song that had been recorded because there weren’t that many recorded [by] 1959. They knew every rock record that had been released.

They were playing them all over and over again and absorbing and absorbing. That’s why, when they started writing, they not only had a very high standard to live up to — which is why their songs were so good right away — but also, when they started writing, they were like, “Let’s try some new chord changes.” You know what I mean? “We’ve been doing these same chord changes for years. Let’s try some new things.”

And so it started there. All of a sudden, an interesting bridge. With songs, they could go somewhere odd, pretty early on. Then the second album was even a little different. And then the third record was a little different. They kept evolving almost to the end, really. And so as they grew, our generation grew with them. And it was just a wonderful, wonderful energy exchange. It was really a part of the fabric of your life.

Yes, it was a soundtrack, but it was also more than that. It was inspiration and motivation. We really, really were a music culture growing up. We didn’t have all the distractions of today. You didn’t have cell phones or computers or video games or TikTok. You didn’t have anything except the radio and three channels on TV.

You may be even one of the people who said it, that when we, for lack of a better term, met the Beatles in ’64, they were halfway through their career as a group. We were seeing a mature group.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. And that’s why, as I go into much more detail in my book, of course, when we saw them, it was an absolute epiphany, a world-changing event. Literally. The term gets used a lot, but this was a game-changer for real. They were so sophisticated that even though they revealed this incredible opportunity, a new world that you had no idea existed, you didn’t exactly say, “Jeez, I think I could do that.” Even though they were just 20, 21, 22 years old, the clothes were different. The hair was different. The accent, of course, their wisdom and wit. Already at that age, they were very, very experienced and very sophisticated and just perfect. The harmony was perfect, the playing was perfect.

That’s why I always credit the Rolling Stones with just about equal importance, because the Rolling Stones come four months later and they’re wearing all different things, their hair is not exactly perfect, except for Brian Jones. And they don’t have any real harmony to speak of really, at that point. They were like the first punk band and they did the same thing that punk would do, years later, by making what they were doing accessible, making it look easier than it was.

A teenager [could] say, “Well, I really don’t know if I could do that Beatles thing, but maybe I could do the Stones thing. It doesn’t look that difficult.” Of course, they were making it look a lot easier than it was.

But making it look easier was important. It was the same thing for punk, really. You listen to the Sex Pistols, and at first glance you might say, “Maybe I can do that.” But the record is phenomenal. It’s a phenomenal record that actually was quite produced. So the Stones were that for us.

Like I say, the Beatles revealed a new world to us and the Rolling Stones invited us in.

I want to give you a chance to talk about the work you’re doing in schools, beginning with something you said about the program. You said, “All I wanted was for every kid in kindergarten to be able to name the four Beatles, dance to ‘Satisfaction,’ sing along to ‘Long Tall Sally’ and recite every word of ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues.’ The rest will take care of itself.” Which to me is profound. But I wonder …

I’ll stick by that too (laughs).

How’s that working out? How has it developed from that conception?

Pretty good. Obviously, everything always goes slower than you hope. It took us a long time just to get it together to the point where I felt confident enough to go public with it, which only happened five or so years ago, after working on it for like 10 or 15 years.

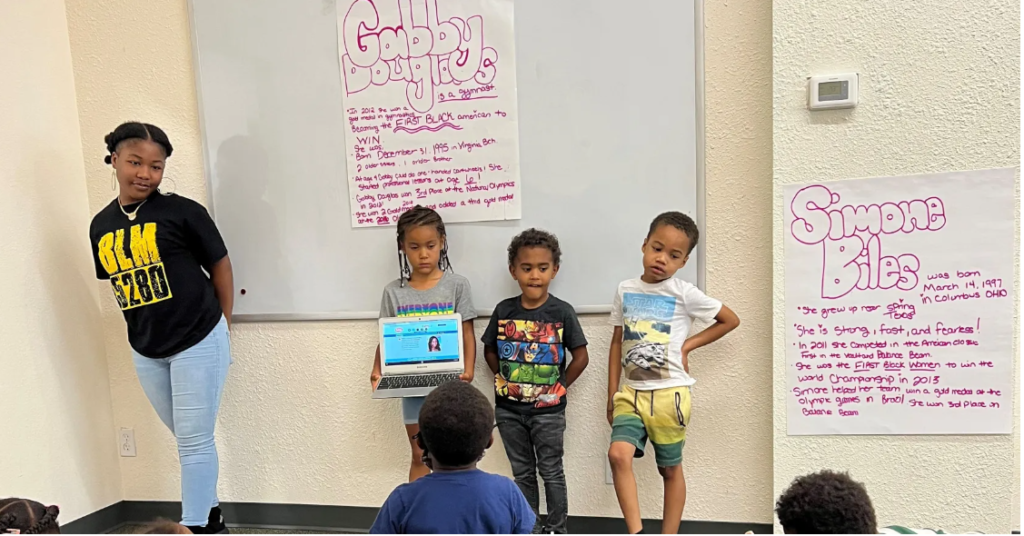

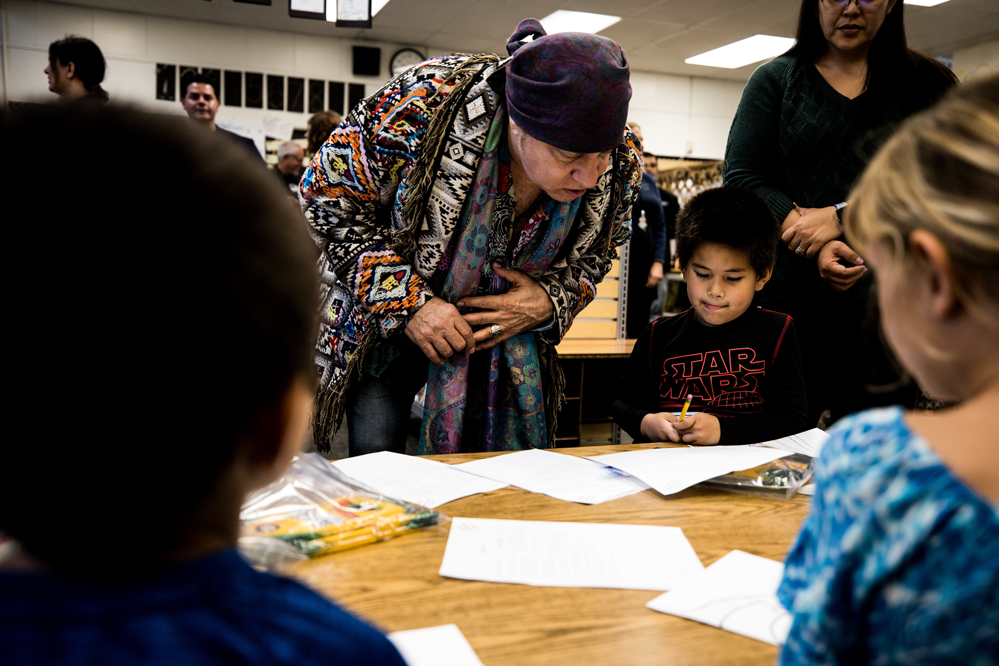

It’s been a long time coming. But we have like 60,000 teachers and 200 partner schools and we’re in every state. I had the opportunity to visit one of our partner schools and, man, it was wonderful to see. I think it was the first five or six grades in this particular school. And the enthusiasm of the kids was amazing. The entire concept here was to do something that would get the kids interested and keep them interested and get them to come to school and stay in school. Judging by the enthusiasm that I saw, it really is working quite well because our whole concept begins with finding the common ground between the student and the teacher.

This generation is only right now. It’s all very, very immediate because of technology.

You’ve got to give them a reason to not look up whatever you were telling them in 30 seconds on their device. “Why do I need you? I got this thing.” So it’s a combination of curation, of selected information that we feel is important and inspirational and motivational, and using what the kids already have, what they’ve already brought with them, which is curiosity and energy and instinct and opinions. They come to school with that, with elements of an identity. And most of our school methodology in the past has been, “Leave all that outside, O.K. Just come in as a blank slate and we’re going to fill in. We’re going to tell you what you need to learn.” And it was a classic, “Learn this now and someday you’ll use it.”

Completely irrelevant.

Over the past couple weeks, the Springsteen Archive agreed to work with you. Can you talk about what that will allow you to do that you couldn’t do before?

Well, it’s more exposure. Right now, our thing is exposure, just turning as many people on to this as we can because we know it works now.

It’s probably going to take another couple of years before we have irrefutable data. But we can just tell because we’re always improving it and correcting it. We get input all the time from our teachers. But we know it’s working. We have absolutely, across-the-board success. So now it’s just a matter of spreading this thing as widely and as quickly as we can because I believe this is going to transform the entire education system. I’m not exaggerating. That’s not hyperbole. I really feel that.

I feel our system is generally antiquated. The machine is so big and so bureaucratic, it can’t adjust fast enough to deal with this new generation. Now we’re into two or three generations of this modern technological world. Still, you can see the system is just struggling to keep up with all of its other problems.

That’s why it was important to us to make sure we made this available for free. Because all the problems begin with, “We can’t afford it,” right? So we were like, “That’s not going to stop us and we don’t want to hear you can’t afford it — because it’s too important.” The future generation is here. We’re going to lose them. I don’t want to hear about money problems when we’re talking about future generations’ quality of life. So we made sure that it’s free for everybody. That way it can spread quite quickly.

We made sure it meets all the state standards. It’s not an after-school thing. We integrate art into the principal disciplines. We add the A of arts into the middle [of STEM], turning STEM into STEAM. We integrate the arts into each of those disciplines.

So that’s a difference between our thing and what people think about art. We think of it in our country as a luxury item. Maybe it’s an afterschool thing or a special school you go to. I don’t think there is a word for art in the indigenous people’s language because art is integrated into everything they do. And that’s the approach we take. It plays on a different part of the brain, the more comfortable part of the brain, not the one that needs to be precise all the time. We like to dwell on the side where there’s no wrong answers. There’s no wrong answers in art, and we like to kind of hang around there, and then make people comfortable enough to deal with the more precise parts of the system.

The last question I want to ask you: What do you see as the legacy of this program 10, 20 years from now?

Well, we keep spreading it. The legacy is the transformation of the education system. It’s the public education that we focus on. Everyone is welcome. We are interested in where most of the kids are and most of the parents are. Most of the really hard-working, underpaid teachers that can’t find enough time to do what they do and end up going out and buying pencils and paper for their classrooms.

So we see this fulfilling our three goals eventually, which is making sure that art in general stays in the DNA of the public education system. Number two, creating a methodology that works for this generation and future generations that have no patience and are a lot smarter and faster than we ever were. It needs a new methodology, and we have that. And the third thing is keeping kids in school and increasing the graduation level and reducing the dropout level, which is just intolerable and scandalous.

We really intend to change that. Because if a kid likes one classroom or one teacher, they’ll come to school. The statistics show that. We want to be that class.

The last thing I’ll offer as an observation is: It’s interesting that somebody like you, not only an outsider, but somebody who even talks of themselves as being sort of like an outcast and ….

You can say, “Moron.” It’s OK.

Oh no! (Laughs.)

You can say even half a moron like me. I should have been a dropout myself. I get it. I know, it’s ironic, isn’t it? It is ironic, but like I say, I feel like I’m the luckiest guy in the luckiest generation.

I think it’s an obligation. I really do feel it’s a responsibility for us to pass along something that was better than we had because we’ve taken all the good stuff. We’ve taken an awful lot of the good stuff, and we’re leaving them a hole in the sky and a poisoned environment and a permanent recession really — all kinds of ridiculous problems in terms of the failures of our society.

So you look around, you say, “Oh, well, what can we do? What do we have control of that we can pass along that’s an apology to the next generation?” So I’m hoping that this is one of the things, along with a couple of my radio formats [that] I hope will long outlast me and improve the quality of life for the next guy.

I mean, what else can you do? What else are we here for?

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Republish This ArticleWe want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

The 74 is a nonprofit news organization covering America’s education system from early childhood through college and career.

As a national news site, The 74 is dedicated to examining the issues impacting the education of America’s 74 million children — and the effectiveness of the system that delivers it. We center our reporting on the teachers, innovators, researchers, school leaders and politicians who shape that education, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. But most importantly, we focus on the students, their parents and their achievement.