Cover photo: Third grader Clark Esposto reads in a window nook of the Swigert International School library. Cover and all other photos by Sarah Huber.

Colorado is one of only 11 states where more than 100 school and public library books were challenged in 2023, according to the American Library Association (ALA).

This represents a surge from 2022, when the state logged its previous record of 56 challenges. The books most questioned in 2023 were written by or about people of color or the LGBTQ community.

Libraries in Central Park have reported significantly fewer complaints than those in Colorado Springs Academy School District 20, where school librarians have been threatened with legal penalties, or Douglas County, where libraries have repeatedly appealed book bans.

But Central Park school librarians are still increasingly circumspect.

Librarians are balancing the free exchange of ideas with putting age-appropriate literature in the hands of students, said Sallie Shultzabarger, librarian at Swigert International School.

Also, in reaction to the recent uptick in book challenges, Denver Public Schools has codified their resource reconsideration policy, or the protocol DPS now follows when a book is questioned.

“The policy makes me feel like Library Services has my back,” Shultzabarger said of the department that manages the district’s audio, digital and print book collections.

Suzi Tonini, former DPS supervisor of collection development, drafted the district’s reconsideration policy in 2022 in alignment with ALA guidelines. Tonini, who is currently a library leadership consultant with Colorado Department of Education, noted that a wise response to book challenges “provides a structured, transparent and fair process for addressing concerns about library materials and safeguards access to information and students’ intellectual freedom.”

Shultzabarger looked to the reconsideration policy last fall when a parent raised questions about a book on sexual development. She recalled that “after I carefully reviewed the content, I did think, following the guidelines related to recommended ages for a book, that this was an informative book for middle schoolers but probably isn’t the best for our student population (preschool through fifth grade).”

Shultzabarger said the experience shows that school librarians want what’s best for kids.

“We order what we think our students will love reading and what will expand their horizons in a way that is appropriate to their age,” she added.

DPS Library Services must approve all print book orders placed by school librarians.

“Selection policies include criteria that provide guidance on selecting library materials that reflect the student population, such as students’ ages, personal interests, identities, needs and reading levels, provide a variety of viewpoints and align with the school or district mission and curriculum,” Tonini said.

“School library materials differ from curriculum resources because they are student-selected and not required reading,” she said. “That being said, parents and guardians play an important role in guiding their children’s reading and library use, and they have the right to determine which library resources are acceptable for their own children.”

Concerns about a resource usually start with a conversation between the questioner and the school librarian or principal.

“A solution might be as easy as putting a note in the student’s account that they can’t check out books on witchcraft, or whatever the concern is,” said Kacie Close, Westerly Creek Elementary’s librarian and xSTREAM teacher (her title reflects her focus on STEM fields and the arts, in addition to her role teaching students how to research). “What’s good for a single family isn’t necessarily what’s good for everyone.”

And, she said, “If you’re going to question a book, please read it first.”

Close curates a collection “that is both challenging and grade appropriate.” She pointed out that although some students can read far above their age level, “comprehension isn’t the same as knowing the vocabulary, so the themes may be above their developmental level.”

Cassie Pretlow, librarian at William “Bill” Roberts K-8 School, agreed. Pretlow reserves a wall of books exclusively for middle schoolers. These books are reviewed for children about ages 12 and up and feature demanding vocabulary, complex themes and nuanced plot development.

Nonetheless, Pretlow said, “families here are inclusive and open to having conversations.”

In fact, a few parents have responded to news about books banned in other school districts by donating those same titles to the Bill Roberts’ library.

If a book is formally challenged in DPS, a reconsideration committee is appointed that includes staff from Library Services, DPS teachers and school librarians who are not connected with the school where the complaint originated.

The person lodging the challenge and the librarian from the school with the book are invited to give feedback, and “everyone on the committee reads and carefully evaluates the book,” said Close, who has been part of a DPS reconsideration committee for a book not associated with Westerly Creek.

Books are evaluated according to Library Services’ book selection criteria. If a resource in question returns to circulation, it cannot be formally reconsidered again for five years.

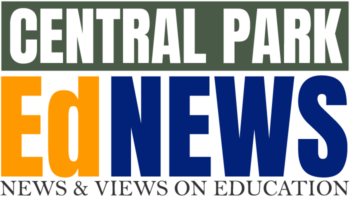

Even as librarians are navigating the brave new world of book challenges, many are expanding how the space is utilized. Some libraries host meetings and display student artwork.

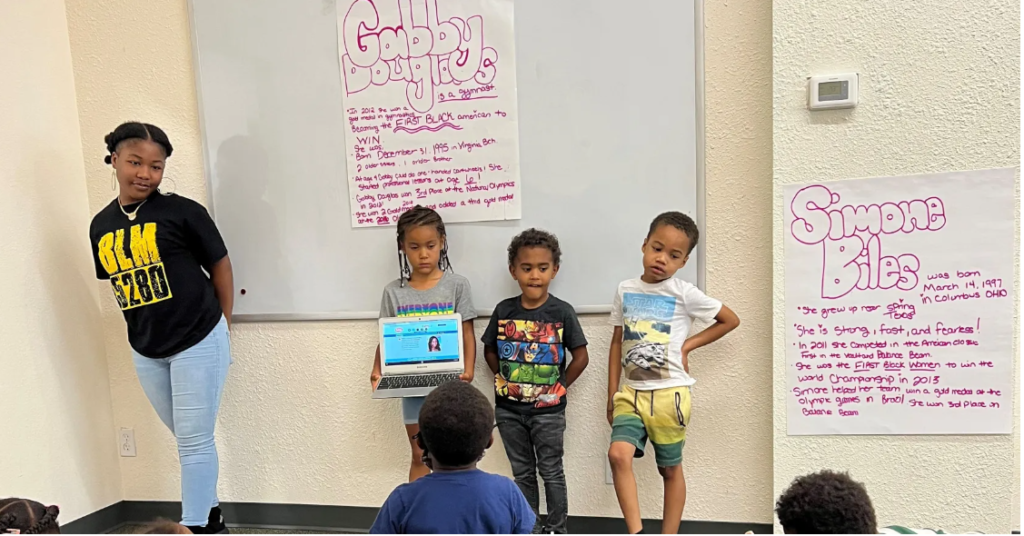

“Our library environment sends the message that this is a welcoming place,” Shultzabarger said. “Everyone is valued here.”

She has transformed the formerly beige room of industrial shelving into a tranquil enclave, with overstuffed pillows, ambient lighting, colorful paper chains and an electric fireplace.

At Northfield High School, librarian Lillie Landa has similarly created a “safe space,” she said, with nearly half the library dedicated to a couch and tables for gathering.

“The library I remember from my school days was tiptoe in, pick your book, the librarian whispers, ‘Shh,’ you tiptoe out,” she said.

That vibe is long gone.

In the NHS library, students eat lunch, the football team plans game-day strategies, student thespians review their lines and always, Landa moves from table to table “as an informal counselor,” she said.

“One student calls me her ‘school mom.’ I’m here to listen, offer encouragement, be a person who cares.”

Landa recently submitted an order to Library Services for more fiction books.

“We are so academically intense that kids come here to decompress,” she said. “Our high schoolers do much of their research online, then pick up a library book to escape.”

As an International Baccalaureate school, Northfield High School is required to maintain a physical library on campus, but for Landa, “having a school library is a want as well as a need.”

At McAuliffe International School, librarian Kim Esbenshade sets books on a “grab and go” shelf in the hall to encourage middle schoolers to read, and students frequently stop by to place books on hold.

“We’ve always had a big push for reading, so though we’ve introduced more tech into the library, like the electronic white boards for presentations, we always go back to the books,” she said. “They open worlds and ideas.”

Yet as books persistently work their magic with students, funding for DPS libraries has decreased. Most school librarians are annually contracted by the district as part-time paraprofessionals. Several DPS schools do not have a library on the premises, and schools with libraries must bridge the funding gap by internal fundraising.

Close said parent volunteers are vital to keeping books in circulation at Westerly Creek, especially since her workday is split between the library and tech lab.

DPS librarians remain hopeful, however.

“When we have books this good, there’s a reason to smile,” said Shultzabarger. “We have more and more books written by diverse authors and for a diverse audience. And if a book resonates with a student, if they can say, ‘I feel seen,’ we’ve done our job.”

(Disclosure: The Foundation for Sustainable Urban Communities supports Central Park schools with grants.)