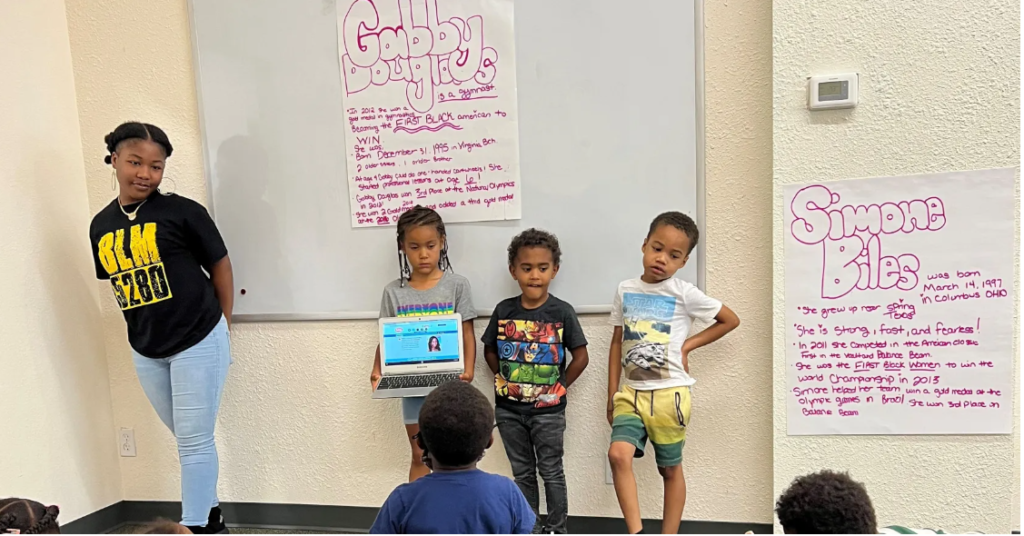

In the photo left to right: DSST-Montview High School students and Brute Force robotics team members Croix Wheatfall, Simon Crine, Jay Belasco, Asher Olgeirson with the team’s main “man,” Moonwalker.

The DSST-Montview High’s robotics team took two of the top four places in the Kendrick Castillo Memorial Tournament on Oct. 14 and 15 at Regis University while exhibiting valuable non-tech skills.

Known as Brute Force, the team fielded two machines, veteran first teamer Moonwalker, and Ankle Biter, a scrappy and endearing newcomer as number two. After the qualification round the tournament’s remaining teams joined alliances formed with three other schools. Ankle Biter took second place and Moonwalker was fourth in the tournament; Ankle Biter beat Moonwalker along the way to earn its finish.

More than 40 schools from up and down the Front Range, Wyoming and Utah entered robots that competed by completing, through remote electronic controls, various tasks while under time constraints.

It was the latest of several top showings for the team. Last year was the second in its 17-year history that Brute Force went to the international championship.

While robotics are first about electrical, mechanical and computer engineering, it is also a program that teaches science kids a range of “soft skills’’ such as leadership/management, teamwork, strategy and planning, perseverance, business practices and fundraising.

For instance, DSST science teacher and lead team mentor, Joey Kistler, said he and his charges were thrilled about the tournament success. But they were especially pleased that they marshalled a lot of different efforts together in a week to build their newest tech teammate.

“Ankle Biter was by far the crowd favorite,’’ Kistler said. “Everyone loved how small and fast he went and how effective he was. Many of the best teams were asking for the CAD (computer aided design) of Ankle Biter so they could replicate it.

“The goal of this competition was to show rookie members what they could achieve, and I believe Ankle Biter was able to do that.”

Brute Force is one of many groups of young scientists. Over 3,300 high school and community teams assemble around the world in anticipation of the upcoming season of the FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) Robotics Competition, a giant non-profit/sport league started in 1989 as a local program to inspire New Hampshire teens in engineering and technology fields, according to a story from National Public Radio. It has grown to encompass more than 83,000 high schoolers in 31 countries.

The performance in the local KCM Tournament was gratifying but it is the equivalent of a preseason game, a warmup for big tournaments coming next spring, the regionals and depending on performance, the international championship in Houston. The tournaments require teams to design and build industrial-sized robots using sophisticated hardware and software technology to play difficult field games against other robots like picking up and lifting cones or other objects and dropping them in an elevated basket

Click here for: You Tube video with DSST-Montview students explaining why they join Brute Force, the robotics team, and scenes of working on robots and competitions. And You Tube video on Brute Force’s 2022-23 season.

Brute Force started in 2007, and as satisfying as victories are, they are just part of the hard work and rewards.

Brute Force has a solid history but was sidetracked somewhat during the disruption of schooling during the pandemic after which the team consisted of only four members. In the last couple years veterans rallied to recruit and this year’s crew boasts 40 boys and 12 girls.

The “build” of the competing robots is central to their work. That involves group decisions on overall design through CAD, crafting a prototype, then a final version of the machine that will carry the weight in matches.

They also fabricate all parts of their robots that requires precise cuts of metal and bracing up to 100th of an inch. The workshop is a buzz of high-speed drill presses and table saws – and safety glasses.

Not to mention the computer coding that will enable the operators to steer the robot rapidly and to pivot quicker than Jamal Murray of the Nuggets.

Philip Szeremeta, a DSST-Montview grad and Brute Force alum, who’s now a University of Colorado engineering student, particularly liked the project-based aspect of robotics.

“I come to better myself (as a mentor) technologically but to also have a good time,’’ he said during a recent Wednesday team workday that stretches for many hours after school dismissal.

But that technological bent has exposed him to a human joy he might not have found otherwise. “I’ve learned I really like working with kids, especially motivated, technical kids.’’

One of his mentees, Jay Belasco, a junior, who wants to go to CU, too, said he had wanted to build robots since attending the DSST Montview middle school. He started on the build team, but then was attracted to the crew that builds what makes all things work – business.

“Both my parents are entrepreneurs so that definitely pulled me in,’’ he says. “And I really like the program management aspect of it.’’

Belasco helped lead the complicated and time-consuming effort to earn Brute Force its IRS 501c3 certification as a legal nonprofit that can solicit tax-free contributions. His writing skills have improved, he says, and he’s more confident talking in front of people.

Then on to making a budget “out of thin air,’’ management of team members, logistics of travel, equipment transportation and setting up “the pit’’ a 10’ x 10’ space on the match floor where the operators run the robots and others repair them between matches. They also want to buy a bigger tool chest and a trailer to haul all the equipment across states for tournaments.

And of course, fundraising through companies, community members, parents and families.

“It’s going really well actually,’’ he says, while adding like the emerging entrepreneur that he is, “we always need more though.’’

Indeed. So far this year, they’ve taken in $52,486 (precision on all levels) but will likely need twice that when all is said and done.

Along with DSST alums now in college, mentors come from the engineering field with area corporations like Jake Salzman at Ball Aerospace, and also a CU grad. “I have a job that I like to but it’s defense contracting,” he says.

He had done some teaching that he enjoyed and “I’d been asking myself: What am I really doing to give back to the community.

“But I do kinda like making more than a teacher.”

Team mentor Kistler, also had one of those higher-paying engineering jobs but, “I gave up that salary. Mostly I gave up the location’’ to be in a school with science kids in Colorado.