(Cover photo: Inspire Elementary principal Linda August, left, and counselor Michelle Hauck walk the school’s “Peace Path” that they use to help students work through conflict and develop emotional regulation. Photo by: Sarah Huber)

Even as the CDC reports a spike in “poor mental health” among teens, elementary school leaders in Central Park are proactively working to boost resiliency in the district’s youngest students.

Schools are juggling funding to hire mental health specialists for preschoolers through fifth graders, investing in social and emotional curricula and endeavoring daily to build an educational culture that fosters joy.

“I believe laying the groundwork in the early years pays off in the long run,” said Michelle Hauck, counselor at Inspire Elementary School. “We teach them that the ebb and flow of feelings is normal, that you can use coping skills to help yourself and that you can ask for help. This is key to long-term success.”

Willow Elementary School counselor Misty Schroeder agrees.

“It’s not like life gets easier in middle or high school or adulthood,” she said. “We prepare kids by teaching them how to name their feelings and how to do conflict resolution. These are skills our students can fall back on for the rest of their lives.”

Denver Public Schools has been introducing more mental health supports since the COVID pandemic, though pandemic-response funding from the U.S. Department of Education—earmarked by DPS for mental health resources—will expire in September.

In an email to families in March, the DPS Department of Mental Health wrote that the district will use the program’s remaining funds “to support the substance prevention and intervention training program.” DPS plans to designate alternate funds for mental health support and, as required by law, will continue to meet the specifications of 504 and IEP (Individualized Educational Plan) plans for children with special needs and learning challenges.

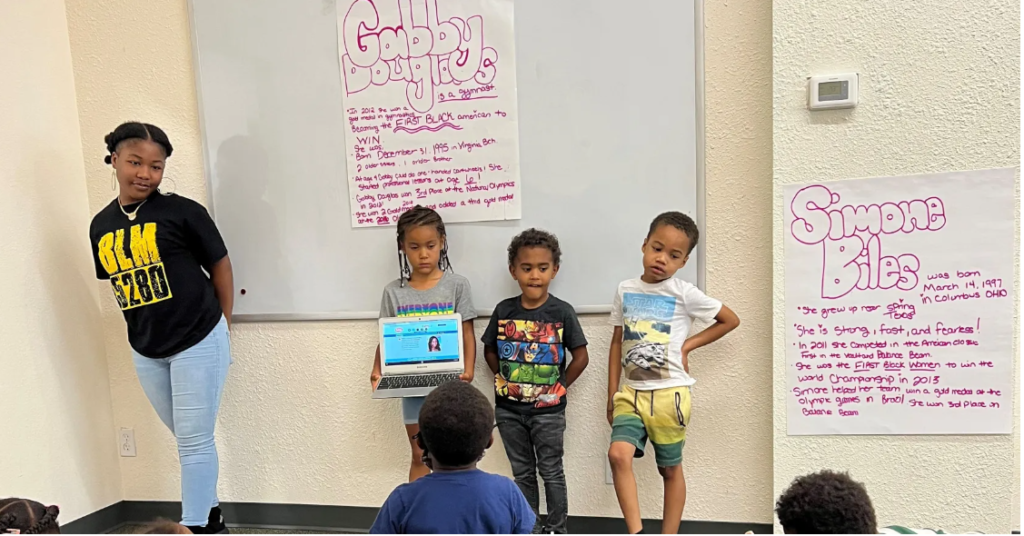

Some of the pandemic-era funding was allotted for social emotional learning (SEL) curriculum. Since the fall of 2020, when DPS returned to in-person instruction, schools have been required to implement SEL for a minimum of 20 minutes per day. This year Schroeder helped roll out a curriculum used in every Willow classroom that focuses on student strengths and equips children with coping skills and tools for conflict resolution and emotional regulation.

“These are the areas where we have seen the greatest needs,” said Amy Infante, dean of culture and equity at Willow.

She explained that “in terms of academics, we are mostly back at pre-COVID levels. Where we’ve seen more of a challenge is the social and emotional effects.”

Anxiety is widespread, as is “students not feeling confident with social interactions,” said Infante, “from not knowing how to clearly navigate or communicate their needs to handling conflict and socially interacting with peers.”

The pandemic is not wholly to blame, however. “Anxiety was in the air before,” Infante said.

That may partly be because “we are more comfortable with the language of anxiety and mental health.

“Some students might say they are anxious and mean they are nervous about something today, which we can talk through using the language of our student strengths, while others are dealing with anxiety that needs more support.”

Social media is another contributing factor to adverse mental health. “There is no time out when you’re always connected,” Schroeder said.

Research documented by the U.S. Surgeon General shows that young people who spend more than three hours a day on social media face double the risk, when compared with peers, of experiencing negative mental health outcomes, such as depression, low self-esteem and eating disorders.

To identify students who might benefit from support with internalizing or externalizing behavior, DPS students and parents are invited to fill out the district’s BASC-3 Behavioral and Emotional Screening System, or “BESS,” at least twice a year. Therapeutic specialists apply these results, alongside conversations with teachers and parents, to create support groups or provide one-on-one care. Students may request support at any time.

“Teachers are the frontline,” said Rebecca Mercer, principal of Isabella Bird Community School. “They work closely with our mental health team and are communicating with parents.”

Teachers are also the ones who usually deliver SEL classroom instruction, such as lessons from “Zones of Regulation,” a curriculum used throughout DPS that develops emotional regulation skills. Counselors help prep SEL for teachers and pop into classrooms to lead targeted lessons, including a DPS-required suicide prevention curriculum presented to fifth graders.

Mercer noted that dedicating 20 minutes during a school day to engage in SEL saves instructional time in the long run. “We take a proactive approach,” she said. “We view and implement SEL as a strategy for systemic improvement, not just an intervention for at-risk students.”

SEL is further integrated into the school day through classroom morning meetings, closing circles, calming corners and restorative practices. Izzi B’s approach, like at Inspire and Willow, is informed by a “deep commitment to ensuring we are meeting the needs of the whole child,” Mercer said.

As for support groups, students generally hone skills in a group for six to eight weeks, and most groups are led by a school psychologist, social worker or counselor.

“Our kids love coming to group,” said Jordyn Walker, social worker at Isabella Bird. “Sometimes they just want to talk to a grownup who will listen.”

She and Stephanie Patton, school psychologist at Isabella Bird, oversee groups on anxiety, divorce, social skills and executive functioning skills, among others. Some of these groups are purposefully developed for Isabella Bird’s population of highly gifted children with a learning or developmental challenge.

“When our kids are connecting in group, they feel less alone,” Patton said. “They realize, ‘I’m not the only one dealing with this,’ and that feels better.”

Isabella Bird also draws on grant funding to offer community-based therapeutic support. (The Foundation for Sustainable Urban Communities has been one of Izzi B’s mental health funders.) Struggle of Love leads groups that delve into leadership skills, and Jewish Family Services provides play therapy.

“It’s natural to proactively engage kids with talking about emotion in elementary school,” Mercer said. “It also serves to de-stigmatize the importance of mental health and gives our kids what they need to be their best.”

Patton has seen a major shift and a lot more interest in mental health support over the course of her career.

“We really get to know our kids,” she said. “Because we are here full-time, we are very aware of what’s going on with our students and can connect before something feels too big.”

Providing all-day mental health support in school, especially at an elementary school, is not the norm in the United States. Central Park principals say they spend copious hours applying for grants and jostling DPS-mandated budgets to keep their mental health team full-time; frequently, PTA and community support shore up the deficit.

Linda August, principal at Inspire, says, “It comes down to staff design: Where do we put our funds? What can get strained if we don’t have the right staffing?

“We are a school with a team of people who provide support. But what does this look like at other schools with more needs? That can be really tough.”

To provide further mental health support, DPS recently partnered with Hazel Heart to connect students with free teletherapy. Students may also access therapy through Denver Health, which has locations in 19 DPS schools, or receive free virtual or in-person counseling through I Matter, sponsored by the Colorado Office of Behavior Health. For those uncertain about where to start, coordinators from the DPS partner Care Solace or the DPS Family and Community Engagement team are available to connect families with mental health support.

(The Foundation for Sustainable Urban Communities awards grants to Central Park schools.)