A little more than a year after ChatGPT was released, tech-savvy educators in Central Park have no doubt that an educational revolution is afoot. But big questions remain about how and when to bring generative artificial intelligence into the classroom.

“There are huge potential benefits to AI (artificial intelligence) in the classroom, and I think we have an obligation to be at the forefront of that,” said Kirk Anderson, director of academic and business systems for DSST Public Schools, a network of 16 charter middle and high schools in Denver and Aurora; four DSST schools are in Central Park – DSST Montview MS/HS and DSST Conservatory Green MS/HS.

Last spring Anderson helped craft guidelines for AI usage within the DSST network with a group of administrators and teachers.

“We saw it coming down the pipeline, and we wanted to get ahead of that,” said Moria Wiedenman, director of marketing and communications for DSST.

They came up with three priorities:

1) Staff and student data must be kept private.

2) Recognize that AI-generated content may be false, inaccurate or harmful and proceed with discretion.

3) Remember that large language models, such as ChatGPT from OpenAI, are based on biased data sets and, again, proceed with discretion.

Concerns about academic integrity related to AI are covered by DSST’s policies on cheating and plagiarism.

Some DSST teachers have responded enthusiastically to the greenlight on the ethical use of AI in school, while others have intentionally chosen not to introduce AI into their classrooms yet.

Nick Wilsey, physics and engineering teacher at DSST: Conservatory Green High School, turns daily to AI to generate ideas for student projects, support multi-language learners, plan lessons and keep on top of grading. “I want students to see AI as a tool that can enhance them rather than something that would replace them,” he said.

Wilsey has observed his students “becoming more innovative by using AI as one of their collaborators.” That’s why he encouraged a team of engineering students who were designing a sequential puzzle to investigate with AI how each element of the puzzle could stimulate different parts of the brain.

Nonetheless, he said, “We need to teach our students that AI is not as good as they are. It can’t replace a human, but we can let it do some things for us.”

What is artificial intelligence?

According to Coursera, a leading provider of online learning to individuals and organizations worldwide, artificial intelligence is the theory and development of computer systems capable of performing tasks that historically required human intelligence, such as recognizing speech, making decisions and identifying patterns. AI is an umbrella term that encompasses a wide variety of technologies, such as machine learning and deep learning.

ChatGPT (Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer) is part of a new generation of AI systems that can converse and generate readable text on demand and even produce novel images and video based on what they’ve learned from a vast database of digital books, online writings and other media, according to a 2023 story from the AP (Associated Press).

Chapin Wright, world history teacher at DSST: Montview High School, is on board. AI is a top classroom tool for him but his students rarely see it in action. Instead, he uses AI to boost his efficiency as an educator, create differentiated learning materials and track classroom patterns to aid him in meeting student needs.

As an example, last month Wright constructed a custom GPT to help students prepare for the new digital format of the SAT from readings they were already analyzing in class.

“This means my students get the benefits of targeted SAT practice without the downsides and drudgery of standalone test prep,” he explained.

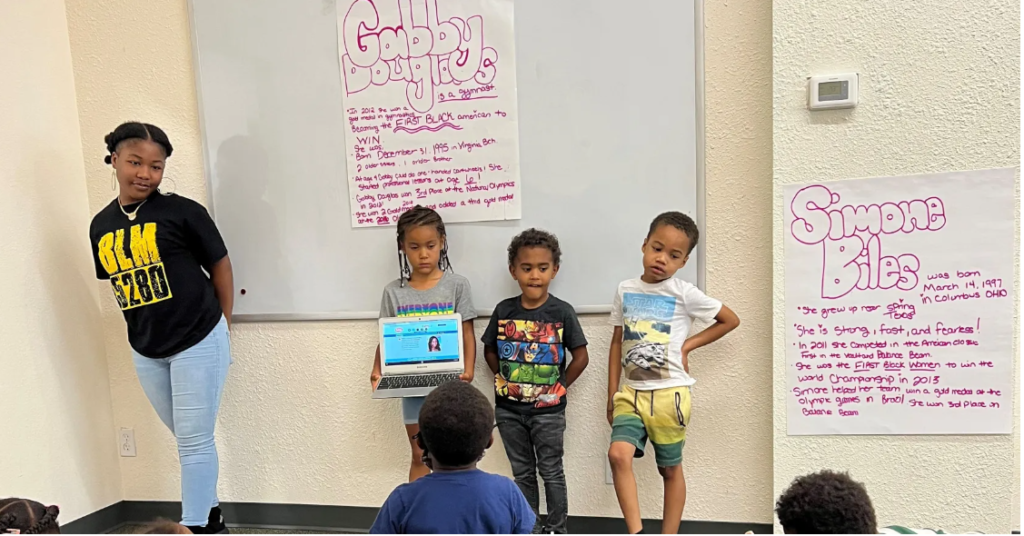

Perhaps most crucially, Wright believes generative AI, if managed carefully, will enhance student equity.

“Just like a lot of tech shifts, there is an opportunity here to either promote equity or exacerbate inequities,” he said.

Educators can utilize AI to “bridge language gaps, provide quicker access to more rigorous texts and connect diverse students with a more diverse curriculum than most teachers could create without AI.”

Otherwise, he warned, “if we don’t figure out ways to integrate and eventually make AI student-facing, we are inevitably going to birth a generation of AI-proficient students and non-AI proficient students.”

Lilia Overmyer, social studies teacher at DSST: Conservatory Green High School, has not been hesitant about exploring AI as a current graduate student at Johns Hopkins University and a recent fellow with a company developing AI for educational purposes.

Yet she has serious concerns about welcoming AI into her classroom.

“It is our responsibility in education to learn how to integrate AI in an ethical way, and one of the most important parts of that is that the adults using and incorporating the tech actually understand this extremely powerful technology and are not using students as guinea pigs,” she said.

In her twelfth grade AP government classes, Overmyer sticks with Socratic dialogue (Socratic dialogue encourages a class to discuss/debate and reach consensus to answer a question.), mock trials, simulating Congressional duties and traditional notetaking (research has shown that writing notes by hand improves memory retention, she added).

More than a few of her seniors have struggled due to “a lost year in education from the Covid pandemic,” Overmyer said, and she hopes to empower them to develop their own ideas before looking to AI as a “crutch.”

PJ Shields, a literacy and composition teacher at DSST: Conservatory Green High School, agrees with Overmyer that AI technology is “not yet ready for the classroom” – and especially a literacy classroom, where the objective is learning to write and think well.

“My experience with artificial intelligence is that you have to be extremely expert in your content and in your intentions before you yield a product that is usable,” she said. “Students are still developing content and skill expertise, and I am still developing expertise with AI as an educational tool.”

Nationally, teachers also seem skeptical. Despite the hype around AI, a new survey from the Education Week Research Center found that two of three educators said they haven’t used AI-driven tools in their classrooms; 37% don’t plan to start, according to the survey, which included 498 teachers and was conducted between Nov. 30 and Dec. 6, 2023.

Shields looks back a good number of years to some of the unintended consequences of nearly unrestricted access to the internet by young people and suggests a more nuanced approach with AI, adding, “I really want us to explore the ethics and the best practices in the classroom with artificial intelligence before we use it with kids.”

Shields’ concerns are reflected in her goal to educate students on media literacy.

“Artificial intelligence is contributing to the endless gobs of misinformation infiltrating the internet,” she said.

Lessons in informational and media literacy equip students with a “sharper eye to sort through the information fed directly into their hands by their phones” and teach them to be mindful of whether they are interacting with a human or AI.

“We need to be careful, keeping in mind the developmental stages of our students, protecting them first and then making sure they are ready for the world that they are going into,” she said. “All of that is at play when we consider artificial intelligence.”

Overmyer and Shields have experimented with AI to evaluate student work, but both said they are able to offer more specific, actionable feedback to students than AI can provide and that they can do so more quickly than they can train AI to follow their rubric. As for worries about cheating, many writing assignments are completed in class these days, often on paper or on laptops with browsers locked.

DSST schools are among the few within Denver Public Schools that provide specific guidelines for using AI in the classroom. Some schools, such as Northfield High School, keep their references to AI to the plagiarism section of the student handbook, in which “ChatGPT/AI software” is prohibited.

Referring to the DSST network of schools, Anderson said, “It’s part of our DNA that we prepare students in science, technology, engineering and math.

“And since AI has already impacted these fields significantly, this is a conversation we need to have as we prepare students to interact with AI in responsible and productive ways in the future.”